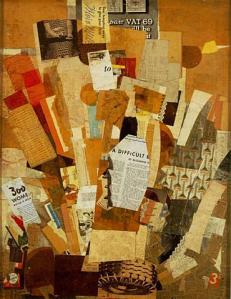

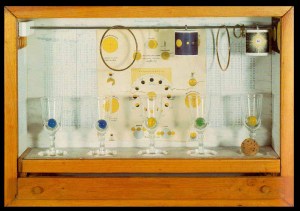

Untitled (Solar Set), c. 1956-58. Construction, 11 1/2 x 16 1/4 x 3 5/8 inches. Collection Donald Karshan, New York

Untitled (Solar Set), c. 1956-58. Construction, 11 1/2 x 16 1/4 x 3 5/8 inches. Collection Donald Karshan, New York

Untitled (Pharmacy). 1943. Construction, 15 1/4 x 12 x 3 1/8 inches. Collection Mrs Marcel Duchamp, Paris.

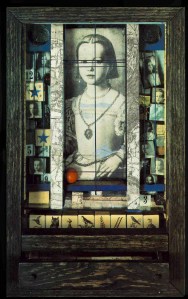

Untitled (Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall). 1945-46. Construction, 20 1/2 x 16 x 3 1/2 inches. Collection Mr. and Mrs. E.A. Bergman, Chicago.

Untitled (Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall). 1945-46. Construction, 20 1/2 x 16 x 3 1/2 inches. Collection Mr. and Mrs. E.A. Bergman, Chicago.

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set). 1936. Construction 15 1/4 x 14 1/4 x 5 7/16 inches. Wadsworth Athenum, Hartford, Conn. The Henry and Walter Keney Fund.

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set). 1936. Construction 15 1/4 x 14 1/4 x 5 7/16 inches. Wadsworth Athenum, Hartford, Conn. The Henry and Walter Keney Fund.

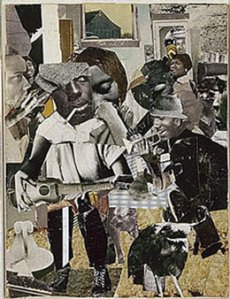

In the fifties and sixties, “assemblage” has emerged as a distinctly American form of sculpture. Like Surrealist objects, a lineal descendant of collage, assemblage–the art of joining unlikely objects or images together in a single context–has as ancestors Duchamp’s 1913 Bicycle Wheel and Picasso’s 1914 Absinthe Glass with Spoon. Because it uses material from the environment and lends itself to eccentric experiments, assemblage seems especially suited to the American temperament.

Like Schwitters, Cornell is able to distill poetry and drama from ordinary fragments. Cornell is . . . attracted to precious fragments–crystal goblets, bits of sparkle, etc. His “boxes” are actually three-dimensional collages, star-maps of a private universe. In fact astronomical imagery is important to Cornell’s iconography. His objects in their new context take on new meanings akin to poetic metaphor. – Barbara rose. American Art Since 1900. Holt, Reinhart and Winston. 1987.

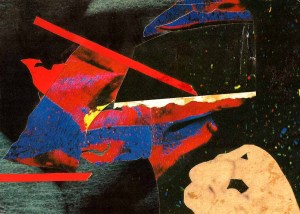

Upcoming . . . Day Eight: Richard Hamilton.